Ever seen someone in a hospital hooked up to a clear bag dripping into their arm? That’s an IV, short for intravenous, delivering fluids directly into the bloodstream. IV fluids are commonly used in hospitals and clinics to hydrate patients, balance electrolytes, and sometimes deliver medications. In this article, we’ll break down what IV fluids are, how they work inside the body, who might need them, and what benefits they offer. Whether you’re just curious or preparing for a hospital visit, this quick guide will help make sense of those mysterious bags and tubes.

What Are IV Fluids?

IV fluids, or intravenous fluids, are sterile liquids given directly into a person’s veins using a small catheter and tubing. They’re used to hydrate the body, replace lost fluids, or deliver medications when someone can’t take them by mouth. Common types include normal saline (salt water), dextrose (a sugar solution), and Ringer’s lactate (a mix of fluids and electrolytes that closely matches blood plasma).

Each type has a specific job depending on what your body needs. Because they go straight into the bloodstream, IV fluids work faster than anything taken by mouth. They’re a staple in emergency rooms, surgical recovery, and even urgent care clinics for dehydration, infections, or injuries.

How IV Fluids Work

IV fluids enter your bloodstream through a vein, allowing your body to absorb them almost immediately. Once in circulation, the fluids spread quickly, helping to balance electrolytes like sodium and potassium, key ingredients that help your nerves, muscles, and cells function correctly. If you’re dehydrated or have lost fluids due to illness or injury, your body might struggle to keep vital organs working.

That’s where IV fluids come in.

Whether replacing lost fluids, helping regulate your temperature, or flushing out toxins, the effects are fast-acting and precise. It’s one reason why IV therapy is often taught early in a nurse practitioner program online or in-person clinical training.

Benefits Of IV Fluids

One of the biggest perks of IV fluids is how quickly they work. When someone is dehydrated or feeling faint, IV fluids can rehydrate and restore balance in minutes. They’re also essential for stabilizing blood pressure, especially during surgery or when someone is in shock. Electrolytes in the fluid help your muscles, including your heart, work properly.

IVs can carry medication or nutrition directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the digestive system. This is a game-changer for patients who are vomiting, unconscious, or too weak to eat or drink.

In sports medicine, travel clinics, and hospitals, IV fluids help people bounce back faster and stay out of danger when their bodies are stressed.

Who Might Need IV Fluids?

A wide range of people might need IV fluids. If someone’s been vomiting, has diarrhea, or is not drinking enough water, IV hydration can help restore lost fluids quickly. Surgical patients often receive IV fluids to keep their bodies stable before, during, and after procedures. Infected people may need fluids and antibiotics to help their immune systems fight back.

Trauma patients, like those in car accidents, often need rapid IV intervention. Children and older adults are especially vulnerable to dehydration and may benefit from IV therapy in some instances. Even athletes and long-distance travelers sometimes use IV fluids to recover from jet lag or intense physical exertion.

Types Of IV Fluids

IV fluids fall into two main categories: crystalloids and colloids. Crystalloids, including fluids like saline or Ringer’s lactate, are the most commonly used. They’re made of water and small dissolved molecules and move easily through your bloodstream and into tissues. Colloids, on the other hand, contain larger molecules like proteins or starches, which stay in the bloodstream longer and help pull fluid into the blood vessels.

Colloids are often used when someone has low blood volume but needs to avoid fluid overload. Crystalloids are generally the first choice for most people because they’re practical, affordable, and easier to manage.

Are There Any Risks?

While IV fluids are generally considered safe, there are some potential risks and side effects to be aware of. Common issues include swelling at the injection site, which can occur if the IV is not placed correctly, and, in rare cases, infection may develop.

Electrolyte imbalances can also occur if too much or too little of certain fluids is administered, potentially leading to complications. That’s why medical professionals must monitor patients closely during IV therapy. They are trained to identify any problems early and adjust treatment as needed.

IV fluids are a simple but powerful tool in modern medicine. They hydrate, heal, and help your body bounce back when you need support. IV fluids can make a big difference if you’re sick, recovering from surgery, or just feeling drained. They’re safe, fast, and used daily in hospitals and clinics worldwide. If you’re ever unsure about needing IV fluids, talk with your healthcare provider – they’re there to guide you.

Here’s a FAQ-style guide titled “Introduction to IV Fluids: What It Is and How It Works”, covering the basics in a clear and accessible way. This is useful for patients, caregivers, students, or anyone looking to understand IV therapy better.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are IV fluids?

IV (intravenous) fluids are sterile liquids given directly into a vein to provide hydration, nutrients, and medications. They’re used in hospitals, clinics, and emergency settings to quickly deliver essential substances to the body.

Why are IV fluids given?

IV fluids are used for:

- Rehydration (e.g., after vomiting or diarrhea)

- Electrolyte balance (e.g., sodium, potassium)

- Delivering medications or antibiotics

- Nutritional support (when oral intake isn’t possible)

- Blood volume replacement during surgery or trauma

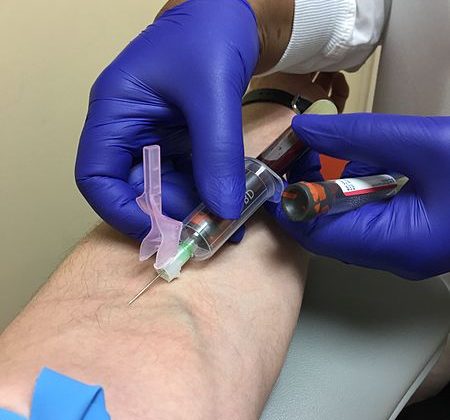

How are IV fluids administered?

IV fluids are delivered through a small plastic tube called a cannula or catheter, inserted into a vein—typically in the hand or arm. The fluid drips slowly from a bag through tubing connected to the IV site.

What types of IV fluids are there?

There are two main categories:

- Crystalloids: Contain water, electrolytes, and sometimes sugar (e.g., normal saline, lactated Ringer’s, D5W)

- Colloids: Contain larger molecules (e.g., albumin, plasma expanders) that stay in the bloodstream longer

What is the difference between isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic IV fluids?

- Isotonic fluids (e.g., 0.9% saline) have a similar concentration to blood and are commonly used for hydration.

- Hypotonic fluids (e.g., 0.45% saline) pull fluid into cells—used cautiously in some cases.

- Hypertonic fluids (e.g., 3% saline) draw fluid out of cells—used for critical conditions like severe hyponatremia.

Are there risks or side effects of IV fluids?

Yes, though generally safe when monitored properly. Risks include:

- Infection at the IV site

- Infiltration (fluid leaking into surrounding tissue)

- Fluid overload (especially in people with heart or kidney issues)

- Electrolyte imbalances

How is the type of IV fluid chosen?

Healthcare providers choose fluids based on:

- The patient’s condition (dehydration, surgery, infection, etc.)

- Lab results (electrolyte levels, kidney function)

- The goal of treatment (hydration, correction of imbalance, medication delivery)

Can IV fluids be given at home?

Yes, in some cases. Home IV therapy is common for:

- Long-term antibiotic treatment

- Nutritional support (parenteral nutrition)

- Hydration for chronic illness

It’s managed by trained healthcare providers or caregivers with proper equipment and sterile techniques.

How long does a person typically stay on IV fluids?

It depends on the condition being treated. Some people receive fluids for a few hours (e.g., ER hydration), while others may require days or weeks (e.g., during hospitalization or for chronic treatment).

Do IV fluids replace the need for drinking water or eating food?

No, IV fluids are used when oral intake isn’t enough or possible. They support hydration and nutrition temporarily but aren’t a long-term substitute for eating and drinking unless medically necessary and supervised.